Archaeological research of the prehistoric necropolis

at Zakotorac on the Pelješac peninsula

Host: Dimitri Medvedev

Introduction:

Delve into the remarkable archaeological find of a Greek-Illyrian helmet, estimated to be around 2,500 years old, unearthed on the Pelješac Peninsula. Positioned near a burial site, this ancient helmet likely served as a ceremonial or votive offering during funeral rituals, echoing a similar find made by archaeologists just four years prior. Recent excavations have revealed this remarkable artifact, adding another layer to the rich historical tapestry of the region.

Historical Discovery at Zakotorac:

Historian Ivan Pamić recounts the inception of the archaeological discovery at Zakotorac, dating back to 2017-2018. Inspired by the Pelješac Chronicle, Pamić's exploration led him to discover intriguing stone structures resembling mounds found in Nakovane. Collaborating with archaeologists Dr. Domagoj Perkić and later Prof. Dr. Hrvoje Potrebica, excavations commenced in 2019, revealing a prehistoric necropolis at Zakotorac.

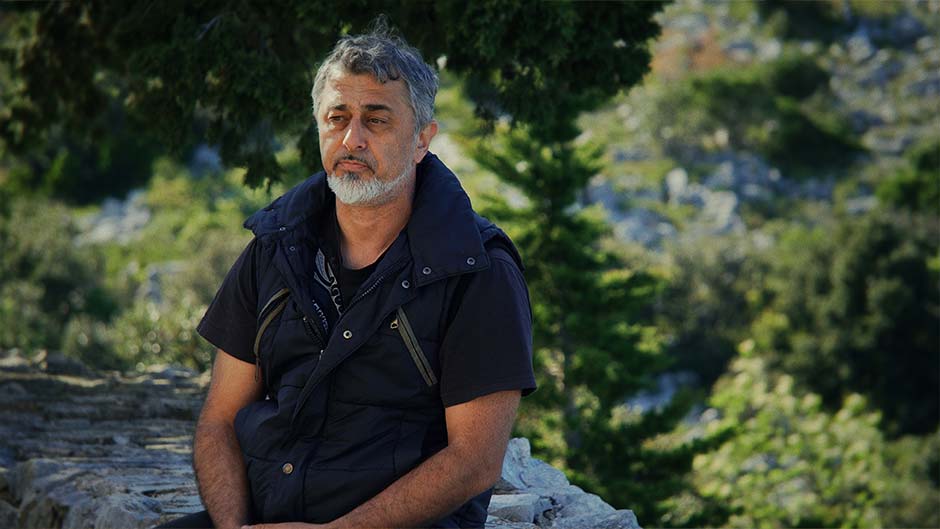

Ivan Pamić

Historian

This was around 2017 and 2018. When I was researching the Pelješac Peninsula for my book, Illyrian Kingdom. Then I visited all those interesting locations mentioned in the Pelješac Chronicle. There, Igor Fisković described almost all prehistoric hillforts that could be found. One of those hillforts was the Kotorac hillfort, above Zakotorac, where I climbed and decided to take some pictures.

At one moment, I looked towards the south and noticed on the saddle of that hill, some regular structures that didn't seem like houses or settlements, so I decided to go there and check it out on the spot. When I descended, I saw that those stone structures were very similar to mounds found in Nakovane. These are mounds that have two or three rings on them, and that immediately intrigued me since such mounds with rings are not found throughout Pelješac. They are only documented in one other place, which is Kopila on the far west of the island of Korčula, near Blato.

I returned the next day, since that day was already ending, I decided to return the next day and carefully record each of those mounds. So, I marked on the map even 27 or 28 mounds with a diameter of less than 90 meters.

That really intrigued me, I saw that it was somehow an important location. Then I informed about my findings the archaeologists on duty, it was Dr. Domagoj Perkić and later prof. Dr. Hrvoje Potrebica from the Faculty of Philosophy in Zagreb.

They were immediately intrigued and came for a field inspection right away.

From that year until the end of 2019 and the following year excavations started.

The excavation of the necropolis in Zakotorac continues to this day, and we have explored a total of three mounds and their annexes.

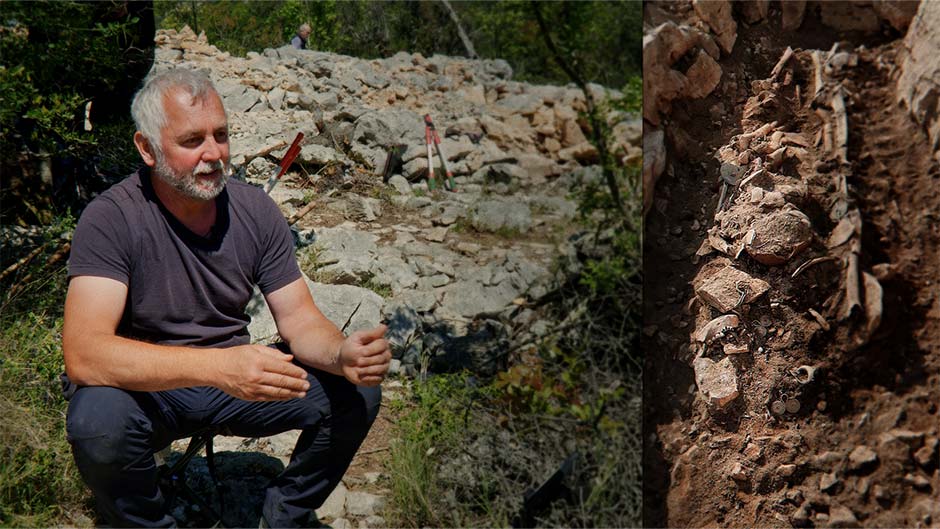

Dr. Sc. Hrvoje Potrebica

Head of the Department of Archaeology at the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb

At this site, two Greek-Illyrian helmets were found in a relatively short period of the last four years. Such a finding is not unusual, that it has never happened that several helmets were found at a single site. However, for example, this type of helmet that we found here, there are about two hundred in the world. In several cases, it happened that at some sites there are more. However, most of such findings are related to some Greek sanctuaries, that is, to some very specific places where these helmets were adapted as votive offerings to the deities. And in this case here what we have, we have two helmets that were placed in some kind of burial contexts, however, they are not part of burial offerings.

People often imagine if you find a helmet in a cemetery that it belongs to a deceased person, that it is part of his burial inventory, meaning that it was on his head or was placed in the grave. With these helmets, that is definitely not the case, because the helmets are not in in an anatomical position, so they are not part of any skull, nor anything else.

They are not even placed horizontally, as one would expect in a burial context. They are placed vertically, so vertically, and one was placed next to one of the walled graves, and the other was placed in a pile where there are at least 8 different enclosed units, some of which are graves, some are tomb chambers, the helmet itself had its own separate space, enclosed by stone. It was fixed with several pieces of stone within that space, placed vertically, with one of them entering the space that is the face opening.

So, it seemed like the helmet couldn't actually move and had its own storage space, like a small chamber with a niche where it was placed. and everything was enclosed with large stones covered by a large stone slab. It is quite difficult for us at this moment to say whether this helmet was connected to any of those burial units within the pile, or whether this helmet is actually some kind of votive offering, some form of cultic practice that related to the entire pile. which was constructed. It's also very interesting that we're dealing with two helmets of the same type.

So, archaeologically speaking, they are in some way part of the same production, however they are different in size. Is it the same workshop that produced simply two helmets of different sizes? Is it about the size having some meaning, either in terms of the amount of bronze and the size of the helmet as when we light candles in the cemetery and sometimes buy a larger or smaller one out of respect or custom towards the deceased, or is it simply a coincidence that at one point they obtained a helmet that was slightly smaller than the other? We'll have to think about that in the future.

Another thing about these helmets, for example these two, considering we're working in the 21st century and often people think of archaeology as something like Indiana Jones discovering a helmet and then running around with it to a museum or something like that and that we, we really enjoy such things, but we enjoy them as parts of a story.

Our job as archaeologists is primarily to tell the story of human communities that lived before us. The skill of an archaeologist consists of two things.

I like to say it's somewhat of a schizophrenic science. One part of our science is humanistic, and the other part is natural science. Although we're close to any television program, we're actually much more like CSI, where we arrive at the crime scene two and a half thousand years late and now we need to reconstruct what actually happened there.

In our work, we use and should actually use the most modern methods provided by the natural science community. This means DNA, isotopes, metal composition analysis, radiocarbon dating. Thorough research with no rush, where we have to determine exactly which item is related to which. For us, context is actually the most important thing.

It's like when you want to do a favor for the police by taking something from the crime scene, washing it, and taking it to the police station, expecting gratitude. That's roughly our relationship with people who use metal detectors. Not only do some of these people steal our heritage, but the disturbance of context seriously disrupts the story for us. Context is much more important to us than the object itself. In this case, with these helmets, the context will allow us to tell a particular story.

It's very important to us that it's not in the grave but on the side. If someone removes it, we'll never know. In this case, we know, and it's a very rare example that in recent years within the last 30 years, two helmets have been found in one place with systematic archaeological research. Which means that the context enables us to tell a particular story. This isn't primarily a sanctuary; it's a cemetery. But the helmets are part of the cultic practice that takes place in this grave. They're not part of the grave goods. So, in a way, we're uniting the idea of an offering to the sanctuary, some votive practice and what happens in the grave. In this context, these helmets have different types. So, that Greek-Illyrian or Illyrian form, as mentioned here, is often especially in the broader public, confusing things. Namely, it is a helmet with a wide opening for the face.

So, it doesn't have any face shield, but it has a square opening for the face. Such a type has actually been known since around the seventh century or even earlier. And, generally, the first phases of the development of that helmet ended exclusively at Greek sanctuaries in Greece. The second phase of that helmet was actually massive, when we look at the distribution maps where these helmets are found, they were found, mostly in Greece, with some very exclusive findings in the north. One of them is in the north of Bosnia, and the other one we were lucky to explore, I'm currently researching that site in Kaptol near Požega, where in the 60s. one such helmet was found which is the northernmost, there is none more northern than that helmet, of Greek production.

Now these helmets functionally had studs around that face rim, so there we know they had some padding, like the helmets used for motorcycles today or anything else, so that the metal wouldn't directly sit on the head and so it would have some softer part that actually compensates for a potential impact, and they had padding so you would put the helmet on your head with padding.

Now, the third phase of development of these helmets, which corresponds to some sixth, fifth, fourth century, so, to this happening here and which belong to our helmets, they don't have those studs. They are still present in terms of a decorative pattern they imitate.

However, they are not there. Which means it doesn't have padding. If it doesn't have padding, then it means it's worn with some sort of undercap. So, you have something you have to put on your head, then the helmet.

Now, such a functional difference actually somewhat suggests to you that it was used by different people. And here is where this situation occurred and the distribution of these helmets is very wide space where Greeks didn't live, but let's call them Illyrians, in their various tribal communities. And because of that, and because of the vast quantity of these helmets, around two hundred or so, three hundred pieces appear across the entire area.

So, it's generally known, but it appears in this wide area, because of that people think it's an Illyrian helmet, so a helmet worn by Illyrian chieftains. And they were. The question is just whether they are the only ones who wore it or if the Greeks continued wear as a part of. And another thing is what we can assume about those helmets of the third phase, there are many types. Which means the market was different. Which means even the production center produced helmets that suited the tastes of individual communities.

So, in that sense, we can say that this third phase can in some way be called Illyrian, but most likely not only Illyrian, but there were others, but unfortunately, due to some dynamics of publication, for example, we know very little about the complete situation. The Necropolis of Pella, the Macedonian capital of Alexander the Great and everything else, has been researched recently.

There is a large cemetery Arhontiko where 140 graves have been excavated, but we haven't been able to see that material for the past 50 years because it's being processed. For example, I have information from scientific circles that there are 40 helmets there of this type, for which we don't know, which will statistically significantly change the picture of this that we know today. As for these helmets specifically found here, they belong to the same type, but they are of different sizes. Again, this tells us that we are not sure if this is intentional, if they have different sizes or something else.

Dimitri Medvedev

Host

And there was also spearheading, right?

Dr. Sc. Hrvoje Potrebica

Head of the Department of Archaeology at the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb

In one of the graves, but the graves, so not on the side, but right in the grave, there was found weapons. Finding weapons in such graves is not unusual indeed. These are relatively common things, especially in male graves. Part of that is that these were communities in which there was a warrior aristocracy, which had an important role in terms of fighters.

However, we also have to consider that part of it is also a demonstration of status. If you were a man of higher status in that community, your badge of authority was actually weapon. So we have to be very careful when we see weapon. Whether this is something that the person specifically used or if it actually belonged in some way to the attire, uniform status like nobles once wore swords as a sign of their noble status, not necessarily functional weapon.

Dimitri Medvedev

Host

This one seems to be the largest to me. I haven't actually seen them all, but it's quite big. The span of this mound over a couple of centuries is quite significant. Is it multilayered, right? Are they on top of each other or is one layer sealed and then a new layer is formed?

Dr. Sc. Domagoj Perkić

Senior curator, director of the Archaeological Museum of the Dubrovnik Museums

So, to start with, there are mounds, this mound is relatively small, it has about... 9 meters in diameter. There are mounds with diameters of up to 40 meters and heights of 8-9 meters. They are usually on hilltops, although there is one towards Vidohovo, towards the water spring, which is approximately that size. So, in that context, this one isn't as large; it's among the largest in this area. In terms of size, it's among the largest in this locality.

And regarding the increased complexity of burial layers, here we have a situation where we have the older cemetery from the beginning, as things stand now, let's say from the beginning, 6th century BC onwards, and onto that older cemetery sits this mound, which we see today, appearing like a ring with three circles.

For example, there's a difference of at least 300 years between the initial burials and the construction of this one from the first burials to the construction of this existing So there is a multy layering, however, even then, these older The graves do not intersect each other, meaning one grave does not go over another, which means those graves were visible on the surface, and they knew exactly where each one was.

Because when they were burying the next person, they didn't come across an older grave, instead, they would be buried beside it, meaning they were visible. However, when they built this last one, the so-called ring-like mound, which looks like wedding cake, with three tiers and three rings, they were built on top of the older cemetery when they buried their own graves, they destroyed the older graves.

However, on one hand, they destroy them because they nullify them, but evidently they took care of those older bones and all the finds they placed in their new tombs. So, for example, in one tomb from the fourth century, all the finds we find, for example, in one of them there were at least 13 deceased individuals.

Of those 13 deceased individuals, we know that some are males, women and children, however, radiocarbon analysis has determined the age of some bones, ranging from around the 9th century BCE to the 4th century BCE. So, they simply collected all the bones, placed them in their grave, and placed their deceased on those bones.

So, on one hand, they destroyed, because they annulled, that older grave no longer exists, but they took care of their ancestors, of their deceased, and those bones weren't thrown just anywhere, but they were placed in their grave. Then all findings go first for conservation and restoration because if these findings including the helmet, but also all other findings aren't conserved, aren't restored, they'll perish.

Regardless of where they stood. They must be protected. So, they have to be conserved and restored, protected from further decay because while they were in the ground they were protected from oxygen or from air and they weren't decaying.

Now that they're exposed to air, exposed to oxygen, that decay goes very, very quickly, so conservation and restoration happen immediately after excavation, which is in principle a long-lasting process. Only after the completion of conservation and restoration follows the ritual, valorization, study, writing of papers, exhibitions, meaning everything else that follows.

Dimitri Medvedev

Host

All these findings are actually a graveyard. It's not like someone accidentally found something in the field, they were buried.

Dr. Sc. Hrvoje Potrebica

Head of the Department of Archaeology at the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb

Those here that we find are all buried. So, it's not just burials, but every tomb we find here is quite unusual. There are multiple layers, multiple burials, there are many people buried in one. What is quite strange specifically for this site is that we don't have the last person. Usually, in such graves, there is a last person in an anatomical position.

So, those bodies that would decompose, the bones would be moved aside and the last deceased would be placed. We sometimes don't have that last deceased person here, but we have multiple burials in one place. So, we're not quite sure about what was the procedure in burials, but they were all buried.

For one person, for now, anthropological analyses have just begun, so don't take this as a complete picture of the whole story, we have very little data in relation to what has already been researched, and we haven't explored even one percent of what we should. For example, for one person, we know that he likely perished due to sword fighting. So there were violent deaths, however, this is a man who was not found somewhere, killed, but he was buried here as part of a burial ritual. We also found swords here. We found cutting weapons, various.

Unfortunately, due to poor iron expectation, we'll have to wait a year, two, three, five, let's see if the conservators, after painstaking and costly procedures, of conserving these pieces of weaponry, will get something that we can recognize typologically as some form of all that, but this year we were exceptionally lucky. Besides the helmet, we also found a Greek sword. Xiphos, a famous type of Greek sword.

However, the question is whether that sword was actually, given its immense value, and exclusivity in such a community, something someone would wield around in practical use or was it a sign of the highest status of a community member or elite.

Dimitri Medvedev

Host

These are broad, aren't they, Greek swords?

Dr. Sc. Hrvoje Potrebica

Head of the Department of Archaeology at the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb

It's a double-edged Greek sword that is relatively short, widened in the middle, and has a crossguard that is somewhat wider and has a rounded handle. These are swords you will see depicted on Greek warrior displays mostly on Greek pottery from that era, somewhere between the sixth and fourth centuries. This is a well-known depiction on Greek vases that everyone reproduces from depictions.

Dimitri Medvedev

Host

How many total tombs do we have now, how many of them are discovered, actually?

Dr. Sc. Domagoj Perkić

Senior curator, director of the Archaeological Museum of the Dubrovnik Museums

Currently, we estimate that there are 27 mounds, not tombs but mounds, but that number basically changes, because some things that appear to us as mounds later turn out not to be mounds, some things that don't seem like anything to us at all turn out to be mounds, so it's just a rough number, but as we conduct excavations, we gradually assign a number to each subsequent one, so that when we finish excavations, then we will have a final number.

Dimitri Medvedev

Host

How often do you find sites like this?

Dr. Sc. Domagoj Perkić

Senior curator, director of the Archaeological Museum of the Dubrovnik Museums

In the area between Dubrovnik and the border with Bosnia and Herzegovina, in Neum and towards the north, we have around 800 mounds, that are recorded, documented, photographed.

Dimitri Medvedev

Host

Over how many years is that?

Dr. Sc. Domagoj Perkić

Senior curator, director of the Archaeological Museum of the Dubrovnik Museums

That spans approximately 2300 years up until the arrival of the Romans.

Dimitri Medvedev

Host

When were first discovered, since 1991 or before?

Dr. Sc. Domagoj Perkić

Senior curator, director of the Archaeological Museum of the Dubrovnik Museums

Basically, when I came to the Dubrovnik Museums, I started listing these sites, so that process didn't go continuously, but whenever there was time or for some interventions, if there was, for example, a highway construction, and one area was visited, then wind turbines were built so another area was visited, then later you connect those areas that weren't connected in the meantime, so it gradually expands and closes, so now we can talk about approximately almost 800 mounds and about 70 prehistoric hillfort settlements.

Dr. Sc. Hrvoje Potrebica

Head of the Department of Archaeology at the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb

We approached the site based on some learning experiences. Our experiences with researching Iron Age sites in the north we somewhat transferred here, and some new approach in Iron Age archaeology that we tried to apply. In a way, to me, it's kind of, not revolutionary, but certainly a much better approach to the whole story that we're trying to apply here in two areas, and that's this area of Zakotarac and Nakovane. And that's an approach to the landscape, not the site.

Because we realized that we're researching point sites and then when it's difficult to understand why something is happening at that place, because we're like some inexperienced person pulling an object out of context, so we're pulling places out of context. We come to investigate this necropolis, but actually, we don't know what's happening a kilometer or two away. In this case, this site located here, based on the structure of the finds corresponds to some things we found at Nakovana and things the team excavated at the site Kopila on Korčula.

These are those unusual mounds with rings that we roughly determined appeared around 500 BC. Before Christ, around the middle of the first millennium BC. Those mounds that are common and that we often see around, that don't have the construction with rings, are actually almost 1000 years older. So, these mounds we're investigating now are in a way a reminiscence, reconstruction of something these people have already seen in their landscape as impressive megalithic construction.

Why did they decide at one point to replicate that monumental way of burying the dead, that's the question we need to see through these communities. One of our ideas, actually, and in what way we're trying to understand these landscapes is through the existence in this landscape where we are now, in Zakotarac, there are also these earlier mounds. There are some sources that could be permanent places of worship in the closer and surrounding area around which all these landscapes revolve.

So, we have some communities that have been continuously existing in a landscape for about 1000 years and the result of that is this. On the other hand, this turning towards monumentality somehow also corresponds to the contents of these graves, the jewelry and everything that appears in the graves, including the helmets we see, which actually show that these communities have a huge economic potential, a power they probably want to demonstrate in replicating the monumentality they see in the landscape earlier.

Which is already in their case local, because they've inherited it for 1000 years. In that sense, when we look at that and connect it with that often Greek part, then that idea of a little more colonial sense, the Greeks come, bring some civilization here, and so far there's nothing here, the Greeks come here of their interest. The Greeks come out of an interest in some market. And the people from this community here are showing themselves as a powerful market. I like to say that those who bury themselves here create a market for colonization in Greece, which happens in the fourth century. They are the reason why the Greeks come here.

They are good customers. The Greeks don't come earlier, because simply there's no one to trade with, no one with whom it's economically viable. If you had to go to Saudi Arabia 100 years ago, you would have sand and camels. But if you come to Saudi Arabia now, they are people who, through oil trade, shake the world. Which means you'll sell 10 Rolls Royces or Helmets there. And before that, you wouldn't sell anything to anyone, because there's nothing to pay with. So that's roughly the idea.

Dr. Sc. Domagoj Perkić

Senior curator, director of the Archaeological Museum of the Dubrovnik Museums

When we talk about mounds, we usually mention Illyrian mounds, However, this is incorrect. Not all mounds can be associated with the Illyrians because they are older than the time when we can talk about the Illyrians. The problem is that our knowledge about the Illyrians as a nation comes exclusively from Roman historical sources, which date back to the first century BC and later, and even then, they talk about previous periods.

So, in the broadest sense, we can talk about the Illyrians in the Iron Age, which means the last millennium before Christ. Before that, we cannot speak of the Illyrians, or any other name for a nation, but rather we refer to them by cultures or periods, such as early, middle, late, Bronze Age, In that context, we define things, but we cannot speak about nations.

We can roughly talk about mounds from around the year 2300. Before Christ until the arrival of the Romans, so roughly until the first century BC. Regarding the Illyrians, we can generally talk about them from the 4th to the 5th century. Before Christ and beyond, in the narrowest sense, perhaps for another couple of hundred years years before, but even that is questionable.

So, mounds and Illyrians cannot always be exclusively linked. At this particular site, Zakotorac, yes, at least for now, but generally, when we talk about mounds, we can't speak so definitively.

Dimitri Medvedev

Host

What challenges is the team currently facing in the field as they continue their excavation work?

Dr. Sc. Hrvoje Potrebica

Head of the Department of Archaeology at the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb

I mean, we've been here for 4 years. The first challenge is, of course, as always, the lack of funds. You see, the conditions in which we're doing this are extremely inhospitable. The karst conditions are surrounded by a huge amount of poisonous snakes, vipers, inaccessible terrain. Almost every step in this karst can mean some injury or anything like that. The work is extremely hard.

Every stone they lift is over 50 kilograms, removing any vegetation requires serious intervention, you need to walk a serious part loaded with material. So, all of that is quite hard. However, it really delights us we've been investing effort for 4 years now, practically with volunteer work. And now there's the situation that here in the team you have top professionals from Croatia.

We have the director of the Archaeological Institute, we have the administrator of the Archaeological Institute in Dubrovnik, and I'm in a way the leader of the consortium. However, here was today a person who will help us in the conservation, who is the dean of the Arts Academy in Split. We have a Curator from the City Museum of Korčula, we have one of the most experienced Iron Age archaeologists in Europe, who is a museum advisor at the Dolenski museum in this place.

All these people actually practically not only finance themselves, but finance the research that's happening here. We, here, after four years, have been lucky to receive some support that we must mention, the municipality of Orebić which has been happening all these years, this year we received significant support from the Ministry of Culture for the first time.

However, researching such things here, we still have to do it voluntarily in every possible way, because money is needed for techniques and services that we need for conducting the research itself, for protecting the sites, but what actually is, that is all just the tip of the iceberg. A huge amount of funds, therefore, 80% of the funds go to analytics and conservation and restoration of objects we find here, to be stored for now in the Dubrovnik Museums, and then we'll see what happens later.

The situation is such that this process needs to continue immediately after the research, and that requires significant financial resources and good logistics.

Dimitri Medvedev

Host

And this collaboration you have with students from Italy, it's actually new?

Dr. Sc. Hrvoje Potrebica

Head of the Department of Archaeology at the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb

That's new. Our team has been conducting research here and on the island of Kočula for several years, so Nakovana, Zakotorac on Pelješac, sites around Lumbarda on Korčula, in a way, a new perception is being created, a new paradigm of interpreting this space, which in a way puts those local communities at the heart of some events dynamics.

They are the ones who are actually the drivers, they are the ones who lead the Greeks to the moves the Greeks make. And when you look at it from that perspective, then you actually get a completely different dynamics, then Greek colonization becomes much clearer, because these are actually moves that correspond to some dynamics on this side.

We have always thought that the dynamics and initiative come from the Greek side, but actually now that we discover these local communities and their dynamics, we realize that the Greeks actually respond economically to what is already happening here. Now, one of these situations is actually this trans-Adriatic communication, but actually here, in this area, we are at the entrance to the Adriatic.

Why I'm saying at the entrance to the Adriatic? Because according to all Greek periploi and customs of sailing and everything else, and in a way, the practicality, anyone who has sailed around Korčula and these areas, knows that the outer side of Korčula and up to Lastovo is not really where you want to be caught in any storm. So, Greek sailing instructions say that you should pass between Pelješac and Korčula. And now, if you include Vis as the first colony, Lumbarda as a colony of Vis, which in a way directly controls the entrance to that channel, you have the gates of the Adriatic, which over centuries and millennia actually dictate the dynamics of what and what will happen north of it.

To understand what is happening on the other side, therefore, these Greeks who actually come from Southern Italy, for us it's actually unknown what is happening and what kind of dynamics is on their side of the area. And that's why we've been trying to get experts from Italy, as well as from Albania, and Greece, now to put together a large international research project, which would actually start to understand the dynamics of those relationships in a different way, the local community dynamics in a kind of universal sense, but also in a specific spatial sense of what is happening, why the Adriatic is in some dynamics of the history of the Mediterranean and Central Europe an important space.

Marco De Pasca

Student of the University of Salento

We are students from the University of Salento, located in Lecce, southern Apulia. We are here for a university project that will also connect the university here in Croatia. We are very happy to be here so that we can better understand the archaeology that is taking place here. I think we should learn more about the connections between our countries.

Dimitri Medvedev

Host

Have you noticed a significant difference in the landscape and findings so far?

Marco De Pasca

Student of the University of Salento

Well, actually, in terms of landscapes, of course, because where we live, the landscape is flat. But actually, there are many commonalities because the geology of the terrain is very similar. Every time you discover something, you feel a wonderful sensation. It's... I can't describe it in words. You can see it in my eyes...You have to be very careful when removing it; otherwise, it will break and scatter into pieces.

Mattia Cucci

Student of the University of Salento

The hardest part is understanding the context, the strategy of application when we have to begin. Often, the context we excavate is very complex.

Marco De Pasca

Student of the University of Salento

You know, archaeology is always changing. You have every day, every hour, perhaps depending on the context. You have a new hypothesis about what it is, of course. That's also the challenging part, actually.

Mattia Cucci

Student of the University of Salento

But that's also the best part of the job because you have the curiosity to understand what you're excavating, what happened. For us, actually, it's a dream to be here.

Marco De Pasca

Student of the University of Salento

It's beautiful here because nature has preserved this site. Otherwise, we wouldn't have all these mounds in the state they are in now. We're also grateful to the professor here, Professor Dr. Potrebica, for the opportunity to be here, and of course, to the whole team.

Dr. Sc. Hrvoje Potrebica

Head of the Department of Archaeology at the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb

These students who are here are students of one of our partners, future partners. We want this to be a solid project, a project that we would actually lead, so the initiative comes from here from Croatia, but top European archaeologists are involved, each in their project, for example, Margarita Gleba who currently leads the Department of Organic Analysis at the University of Padua, one of the largest world experts on archaeological textiles, she works with Greek textiles, Tutankhamun, such things, would be part of our project.

The professor of these students who works at Salento and Lecce, Francesco Meo, would be one of those collaborators. And many people from our side of the Adriatic, so we would actually in a way create a large consortium of researchers who would, both formally and financially, informally in some long-term period, the next decade actually try to answer some of these questions.

Dimitri Medvedev

Host

Alternatively, then students from Croatia also go on Italian sites?

Dr. Sc. Hrvoje Potrebica

Head of the Department of Archaeology at the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb

This is the first year that two more colleagues have come ad hoc to our research and students from Croatia will definitely go there. And this year the European Archaeological Congress is in Rome, so it's a congress of the European Archaeological Society, there will be over three and a half thousand archaeologists from all over.

Already our partners from Italy together with us are organizing one scientific session where our potential partners will also present. These our students from our side and theirs, we'll try to somehow get them to attend one big international conference one of the largest archaeological conferences in the world this year, to feel a little bit that atmosphere and some high world archaeology. And on the other hand, this year there will be a congress of the Croatian Archaeological Society on Korčula, to which we always invite one of the international partners.

The theme of that congress is the archaeology of the southern Adriatic, the gates of the Adriatic in a way, and there we will also invite these partners from Italy to join us, and we have already received a number of invitations where we will send our younger people to such experiences in the southern in Italy, and also our cooperation visits to each other's universities. I've already been to Padua this year, my colleague will come to Korčula, this professor from Lecce will visit us very soon, so we're constantly rallying in some way and networking that cooperation which is, well, for various reasons, in recent decades actually simply did not exist.

Dimitri Medvedev

Host

Why Dubrovnik museum actually, because these finds all go to Dubrovnik museum, is that correct?

Dr. Sc. Hrvoje Potrebica

Head of the Department of Archaeology at the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb

That's right.

Dimitri Medvedev

Host

Or first to Zagreb?

Dr. Sc. Hrvoje Potrebica

Head of the Department of Archaeology at the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb

In Dubrovnik. This way, with the dynamics of the finds, namely we must carry out restoration and conservation procedures. Our first concern is cultural heritage. So, the moment we establish the context, finish with CSI, we must care about cultural heritage, about the objects we have excavated, not to harm them with our research.

So, that restoration and conservation process we must start as soon as possible. Processing, analysis of finds is part of that process and we do that in places where we can achieve the best conditions for that. Naturally, this also depends on financial possibilities, the dynamics, what we can do where. And the equipment that individual places dispose of. So, where are they going now?

First they go to the Dubrovnik Museum, where they will be officially inventoried and stored in some future, that is. The official storage is in the Dubrovnik museums, the Archaeological Museum. And before and after that, they will very likely go through conservation and restoration procedures in various laboratories that, based on their equipment, can provide the best service. That's what is currently in progress.

Now, actually, in this area we don't have a museum institution. The first museum rule is that the finds should be closest to the discovery site. However, that is one of the criteria. The other criterion is that they must be as close as possible to the discovery site under conditions that are suitable for preserving such finds. We, closer than Dubrovnik, don't have a place that can provide preservation conditions for such finds.

So, Dubrovnik is the closest place, the place of discovery that can provide such conditions. In case something is organized in the meantime, and there are some initiatives, to establish a place where these finds can be preserved closer to the site, then it is very likely that an agreement will be reached with the Dubrovnik museums where one of these collections specifically will be exhibited closer to the discovery site. Of course, this requires very strict professional conditions to be met for that to happen, so I think we're still in some phase of future plans there.

Dimitri Medvedev

Host

When we passed through here, there are a couple of settlements. In each of those settlements, there are two, three families. Just one family, I think, living there. We don't have many settlers here, but these graves indicate that there was quite a bit of life here. It was quite inhabited.

Dr. Sc. Hrvoje Potrebica

Head of the Department of Archaeology at the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb

So, when you look at aerial photos from the 1960s, this area that to us looks like untouched forest was completely cultivated. These were all plots that were in use and cultivated. When you look at lidar scans of the forest across from us, it's actually parcelled into boundaries and in principle, there was quite intensive agriculture there. Of course, at the moment when that agriculture was no longer profitable as an economic venture, the population withdrew. It's not just a situation of having periods of two and a half thousand years.

We have a situation that in the last 100 years or 50 years has changed drastically. And such cycles of changes in the use of space often change. In today's economic dynamics, tourism and sustainable development are somewhat something that stimulates what's going on. It's a path that actually has no other choice if we want to think long-term.

You have Pelješac here with fantastic wine production. The other day our friends, winemakers from this whole area, usually, archaeologists and winemakers are great friends. We talked with them a bit. So, that legendary winemaking which is renowned here on Pelješac is being integrated into communities that have actually proven their status in a way through feasts. In their burial inventories, we find imported Greek drinking pottery at these feasts.

So, when the concepts we have here in local communities are combined. So, in local communities from 2500 years ago and the resources we have today. We can, in a way, not invent stories but rather offer our perspective, our reminiscence, our replica of something. Just as these replicated the monumentality of earlier mounds with their own mounds, we can replicate all of this with our own gastronomy culture, in the context in which they are located.

For example, a walk through such a landscape, where you will visit the church at Kotorac, where you will go to the spring in Vidohovo, come to visit this site which will last be an hour or two, with a very interesting story and in some way consumption of local gastronomic and oenological products provides one thing that is irreplaceable, which is unique, which has its own brand that you can't get anywhere else.

And that's something, for example, that you can do all year round. It's not tied to any specific season like summer or anything else. The availability of that is easily achieved in terms of The availability of that is easily achieved in terms of hiking and biking trails and everything else. So, this is a resource. People often think that investing in research or culture is an expense.

Exactly, it's actually an investment. If we don't utilize the resource we're creating here through exploration for the benefit of local communities, ultimately, why aren't there more people here? Because three or four families can live off of Vineyard. However, if such a situation arises, then a lot of the economic niches from which people can have a quality life without jeopardizing the landscape they are in.

The community strategy. Communities that want to endure in one place, like the one we know has been here for 400 years, not only that it has been here, these people, when we talk only about these mounds that we recognize, so not about the continuity of the old mounds, but only about these new mounds. So, these new mounds have a continuity of burial for about 400 years, around there.

So, we have a community here that constantly plays with the landscape, successful adaptations, must observe, especially in a time when, let's say, the power of influence on the landscape was relatively small. You couldn't make some drastic moves that would immediately bring results. What we are used to, I'll just level something now, build a hotel and tomorrow I'll get my investment back.

They had to act strategically, anticipating what the landscape would do to somehow gain an advantage. So, if you want to endure for a long time in a certain area, then you will invest in some things that do not bring benefit at the moment, but give you, as they say in chess, a positional advantage for the days to come. And that's what is being done. You will build mounds along the way.

These big mounds, old mounds. Why? Because in this way, if you build them along the way, you mark the space, you place yourself in the landscape, in a way you occupy space, and on the other hand, it's a method of deterring opponents. Anyone passing through that space, looking at those mounds, knowing the effort that has been invested, realizes that a community that can invest so much effort in something that doesn't bring direct benefit, has a good economic margin for that.

Which means it's a powerful community. On the other hand, the continuity of that, you realize that people have been burying here for 200-300 years. And if you intend to sell them some trick, you have to be aware that for 200 years no one has succeeded. So, they've probably seen whatever you have to sell. You have a completely different attitude and respect towards such people.

So, investing in something is basically a very strategic game. Where a person must keep in mind some long-term goal, and every move is actually a move that leads to that goal in some way. That's like, if you're watching top chess players, then Sometimes you don't understand why they made a certain move. Why they sacrificed a piece. And that's simply because you don't see the whole plan in their mind. And sometimes, as archaeologists, we find certain situations very puzzling. In principle, 90% of archaeology is common sense, especially when it comes to prehistoric communities.

They will do things in the simplest, most efficient, and most cost-effective way. Why don't we see it? Well, that's our problem now. Obviously, we don't have the bigger picture. When something seems strange to us, we're looking at it from the wrong angle. That's our problem, not theirs. Surely they didn't complicate their lives there where they don't need to, because they simply didn't have the opportunity. Each mistake in their strategy meant actually, in a way, the destruction of the community.

Dimitri Medvedev

Host

As we wrap up our time here, let's remember that each discovery adds another layer to our understanding of the past. It's not just about unearthing artifacts; it's about piecing together stories, connecting cultures, and unraveling mysteries. With every careful excavation, we come closer to unraveling the secrets of our shared history.

In conclusion, our time spent here delving into the world of archaeology has been both enlightening and rewarding. From the rugged landscapes to the delicate artifacts, each moment has offered a glimpse into the rich tapestry of human history. As we prepare to depart, let us carry with us not just the knowledge we've gained, but also a profound appreciation for the tireless efforts of archaeologists past and present. May our journey continue to inspire curiosity, foster understanding, and deepen our connection to the remarkable civilizations that came before us.